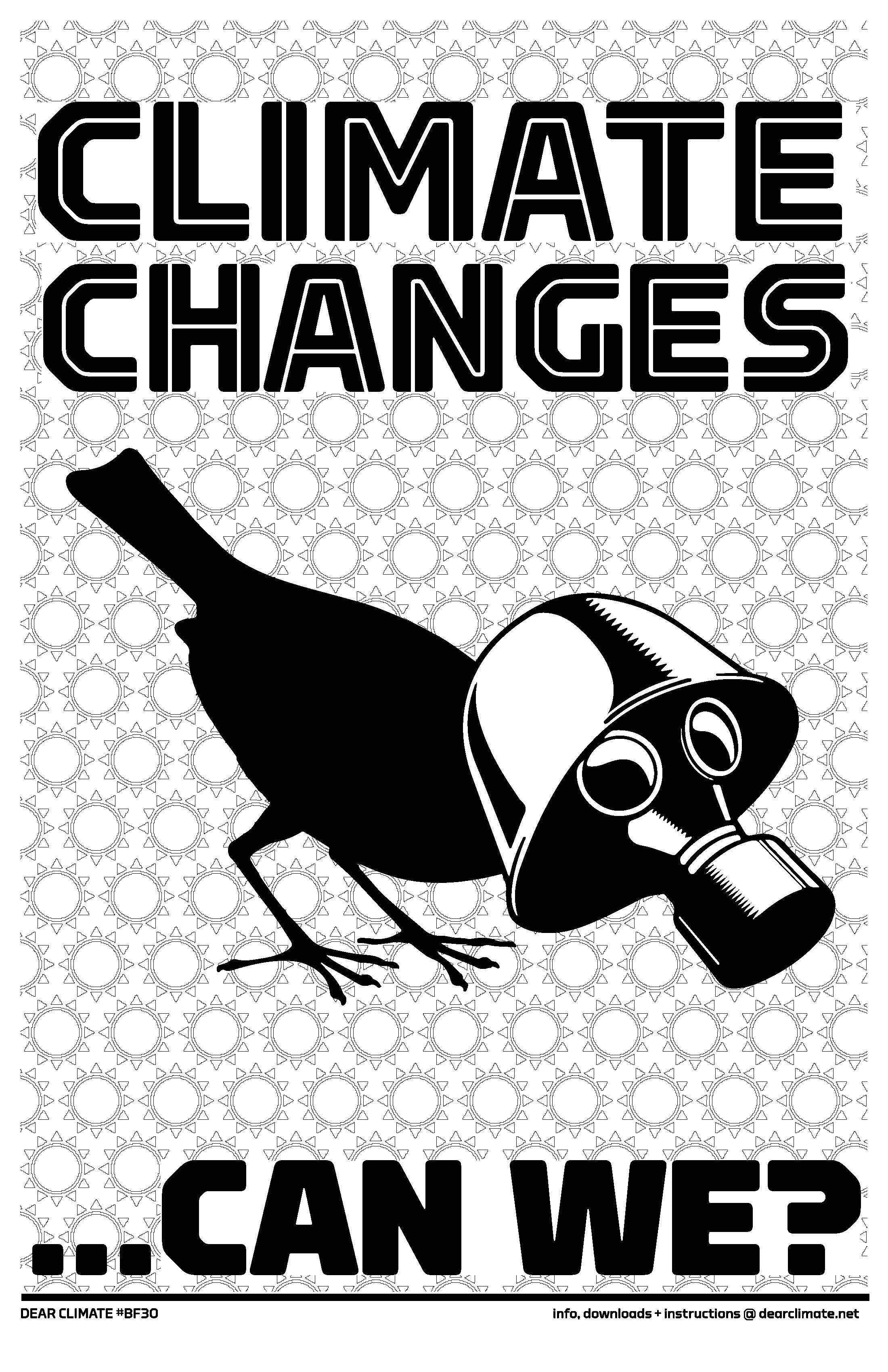

SIX ARTISTS ON CLIMATE

Dear Climate (U Chaudhuri, F Ertl, O Kellhammer, M Zurkow), General Assembly, 2018. Courtesy of the artists.

The reality of climate change is unwavering. It seems as though each day brings another extreme weather event, a newly extinct or endangered species, or alarming fresh data on ocean acidification or shrinking ice sheets—which is to say nothing of the damaging political denials of humanity’s impact on Earth. We’re saddled with the questions of our own species’ twisted design: What can be done? What should we do?

In “Indicators: Artists on Climate Change,” an exhibition at Storm King Art Center in the Hudson Valley, a diverse roster of artists offers ways to think through those very questions. Storm King sought for “the exhibition to be artist-led in its messaging,” according to Senior Curator Nora R. Lawrence, and in that spirit, we asked some of its local participants to illuminate environmental issues as well as reflect on their own relationships with the great outdoors. Here’s what David Brooks, three members of the collective Dear Climate (Marina Zurkow, Oliver Kellhammer, and Una Chaudhuri), Gabriela Salazar, and Hara Woltz had to say. —Haley Weiss

What is your fondest memory of being outdoors?

David Brooks: I have too many of them to possibly list! So I’ll describe one of the earliest more momentous: I was 16 years old and was visiting my brother in the Florida Keys, where he had recently moved. He was house-sitting for a friend that lived on a channel on Big Coppitt Key, and he had a kayak. I went out one day on the kayak, without any food or water, or even a shirt. I just headed straight out into the ocean, I kind of just went for it. I had the wind at my back and it was just 24 hours after a hurricane had moved through the Gulf of Mexico, so the waves were quite high, swells were rolling and the currents were strong. I remember paddling for a very long time without even looking behind me or where I was going. When my common sense came back to me I looked back and saw that land was now back at the horizon. I was many miles out at that point. And when I tried to turn the kayak around, the winds and waves were so strong that I couldn’t even turn the boat. It took quite a while to figure out how to shift my weight to even get the boat pointed back to land. And once I did, I paddled like hell for many hours straight, without stop, with all my strength, to get back to the safety of the grass flats behind the Keys. Needless to say I was exhausted and just kind of drifted a bit across the grass flats, until the sun started to set. And that of course is when all the activity starts up. The food chains and interrelations start playing themselves out before dark, like an epic drama. As this was in the grass flats, it was so very intimate with all details in full focal length. Watching the stingrays, bonefish, barracudas, nurse sharks, boxfish, egrets, least terns, frigate birds, and baitfish all interact, one could apprehend the evolutionary impulses and pulsations coursing through all this non-human life. It was as though witnessing the millennia of evolution itself, making itself viscerally present in the moment. These scales of time that dictated such evolutionary relationships amongst so many life forms was felt, not thought. From this moment, a complete paradigm shift ensued for me, in which all of human history was for me dwarfed by something infinitely more profound, and squished into the duration of a breath, or at least the duration of one feeding frenzy at dusk.

Marina Zurkow, Dear Climate: The smells of pines, drying grasses, animals, soil.

Una Chaudhuri, Dear Climate: Mud squishing up between my toes, becoming amphibian.

Oliver Kellhammer, Dear Climate: A summer afternoon in Southern Ontario when I was a boy, standing barefoot in the ripples of a river, fishing. There were turtles basking on a fallen log. A scarlet tanager flew by.

Gabriela Salazar: I grew up in New York City, very close to Central Park. I was in the Park at some point or another almost every day. I believe having access to this green oasis in the midst of the hectic and hard city kept me sane as a young person. It also gave me a great perspective of the power of human foresight and ingenuity. When the Park was designed and built, what is now Midtown and Upper Manhattan was almost all farmland and a few villages. To see in the 1840s what carving out so much public green space would mean, back then, and then go ahead with such a momentous (and expensive and controversial) public work… It’s the kind of hubris that we still have as a species, but unfortunately we don’t apply it with nearly as much lucidity.

Hara Woltz: I have many fond memories of being outside. One in particular that stands out was during a research trip to assess the health and habitat of a population of giant tortoises on Española Island, Galápagos. The population of Giant tortoises on Española Island once numbered approximately 3,000, but centuries of exploitation and habitat destruction reduced population sizes to approximately 13 individuals by the 1960s. At that point, the 13 remaining tortoises were transferred to an off-site breeding center while introduced goats, a major threat to tortoise survival, were removed from the island. A reintroduction program has transferred offspring of the original tortoise population back to Española since 1971, and the population of tortoises has continued to increase. During our trip the weather had been very dry. One night it poured rain. Around sunrise, we started climbing and slipping over wet rocks to reach our study site. The colors of the ochre grasses and slick, dark lava in the landscape were fantastic and along the edges of the path, giant tortoises gathered and drank rainwater from depressions in the lava. That morning, we found a year old tortoise that wasn’t marked. A lack of mark signified that it had been born on the island and not in captivity. To participate in a successful restoration project, and to spend time sitting in the wet grass after the rains with a young tortoise, drawing and noting and wondering about the life of that being, made for a pretty great moment.

David Brooks, Permanent Field Observations, 2018. Bronze, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson.

David Brooks’s site-specific “Permanent Field Observations” are an intervention in which the artist created cast bronze duplicates of natural objects he found in the woods, and then placed his sculptures alongside their original counterparts. While the organic objects are subject to changing weather patterns and decomposition, his replicas will likely survive far into the future. Together they speak to how humans, in a very short period relative to the Earth's existence, have dramatically altered the planet's trajectory. Our impact will be felt long into the future, likely outlasting many species living today.

Are you an artist or activist first?

David Brooks: I am an artist first and foremost, which might, therefore, also mean I am an activist by default.

Marina Zurkow, Dear Climate: Activator.

Una Chaudhuri, Dear Climate: Enigmator.

Oliver Kellhammer, Dear Climate: Splitsville right down the middle.

Gabriela Salazar: I wish I could claim “activist” but I don’t think I do enough. However, I do think the urgency of addressing human-caused climate change is more important than the work almost any of us do, including my work as an artist. I was honored to be able to create a work at Storm King that hopefully helps bring awareness of the ramifications of our (in)actions; specifically the materials we use and consume, and the inordinate effect of climate change on island populations like Puerto Rico.

Hara Woltz: I’m an artist, but I’m not sure that I can internally label and cleanly separate these two things from one another. My work is the process and product of how I examine, question, observe, respond, and bear witness to the things that I care about. I’m emotionally stirred and intellectually fascinated by biology and ecology. Right now, I am profoundly concerned about the destruction of ecological systems and loss of species. At this point in time, we are all called to be activists of one sort or another if we care even remotely about the biota and systems of this planet. I try to contribute, and I'm grateful to my friends and colleagues and others who are full-time activists.

Hara Woltz, Vital Signs, 2018. Weather station, painted aluminum, mirrored aluminum, and wood, 20 x 30 x 30 ft. Courtesy of the artist. Photos: Jerry L. Thompson.

Hara Woltz’s "Vital Signs" is an interactive weather station. The design on its nine elements references Arctic ice core samples. The white area decreases 13 percent from cylinder to cylinder, the same rate at which Arctic sea ice is predicted to decrease per decade (based on data from 1981 to 2010). Each cylinder also gains height as its white area lessens, in an expression of the concurrent 33 mm. sea level rise expected per decade. In the center of the circle, the instrument at the top of the pole gathers real-time climate data. As a unit the installation points to how climate change's projected path is inextricably tied to our daily lived experiences of place, right here and right now.

What is your greatest concern in the Anthropocene?

David Brooks: I’m still uncertain about us settling on the term Anthropocene. On the one hand, it does paint a broad stroke of consciousness around a fraught world of our own making, hopefully instilling a sense of grave responsibility and agency. However, on the other hand, the term “Anthropocene” anthropomorphizes the entire planet in the same broad stroke of hubris that is arguably the source of the very ills it attempts to address.

Nonetheless, it is our levels of consumption, simply put, that drive us to the brink of circling the drain, and consequently dragging a bunch of other species down with us. To acknowledge or ignore the consequences of anthropogenic impacts on non-humans is an ethical question that will determine the longevity of our species.

Marina Zurkow, Dear Climate: Humans.

Una Chaudhuri, Dear Climate: Suffering.

Oliver Kellhammer, Dear Climate: What they said: human suffering and also the mass extinction of species. Both suck.

Gabriela Salazar: I’m concerned that we humans continue to have too much faith in our own inventiveness. To clarify: I have a lot of hope for human problem-solving—technologies in wind, solar, and energy efficiency continue to expand and should be expanding even faster if they were properly funded. But faith in some quick fix that we’ll be able to deploy just when things look bleakest? No. Too many expect the disaster of climate change to be solved by something that doesn’t yet exist, and that in the meantime we can just continue on as always.

Hara Woltz: The annihilation of species and the disruption of ecological systems. I’m concerned about this from a biological perspective and also from a philosophical perspective. I’m concerned about our psychological disconnect from many of the systems and life forms of this planet, the lack of concern that so many people have about this, and the turning away from scientific literacy and critical thinking that pervades much of our culture. It’s hard for me to understand because I find so much worth wondering about and working for in the life forms surrounding me. I just came back from walking through a dark wetland teeming with fireflies. To paraphrase Oliver Sacks, to have been a sentient being on this beautiful planet for even a day is a tremendous privilege. I’d prefer this beautiful planet to continue on as a habitable and shared home for humans and non-humans alike for a while longer.

Gabriela Salazar, Matters in Shelter (and Place, Puerto Rico), 2018. Coffee clay (used coffee grounds, flour, salt), concrete block, wood, and polypropylene mesh tarp, 12 x 16 x 20 ft. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson.

Gabriela Salazar’s “Matters in Shelter (and Place, Puerto Rico)” is a structure that the artist built following the ruinous impact of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Its floor is made of concrete, a material used for shelter against the elements that also generates significant carbon emissions, and its tarp is reminiscent of temporary housing measures used following tropical storms. Additional blocks in the space were created using a coffee-based clay that will disintegrate and be replaced by Salazar over time—a reference to the coffee farm upon which the artist’s mother was raised in Puerto Rico, and the act of rebuilding something that, without massive cultural shifts, is sure to be destroyed time and time again.

Are you optimistic about the future of the Earth?

David Brooks: The Earth will be fine. It’s the biosphere and our dragging others into extinction that is the question. History has thus far shown that the Earth has encountered many other destructive forces that have challenged its life systems. The real question for me is whether we have the right to do so. We have an ethical compass about us. That compass tells me that unsuspecting non-humans do not deserve the full brunt of anthropogenic impacts (ultimately leading to their extinction) if (and IF is the operative word here) we are able to see and understand the difference between their natural state of life versus their compromised state of life due to our actions. If we feel, collectively, as a society, that it is okay for the Florida Panther, the Red Wolf, or the Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow to go extinct on our watch, due to our actions, at our convenience of not making change, then it will follow that we too will go extinct sooner than later for failing to recognize our interrelationships with these very species. The acknowledgement and safeguarding of the interrelationship of all life is tantamount to the continuation of human and non-human life as we know it. Though many biologists already consider us to be a debt species, meaning it's just a matter of time before we bring about our own demise.

Marina Zurkow, Dear Climate: The Earth will be fine—a brief event in Earth’s geological history is 20,000 years.

Oliver Kellhammer, Dear Climate: Ultimately yes, but not in the short term.

Gabriela Salazar: Optimism is in short supply right now. The policies being enacted in the United States are in direct opposition to where we need to be going to even have a hope of slowing climate change. The amount of carbon already in the atmosphere will continue to wreak havoc even if we completely stopped burning fossil fuels tomorrow. As a culture we have been brainwashed into thinking it’s our right to consume whatever we want.

Hara Woltz: It depends on the day. Today, after spending some hours in the forests of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies with a group of inquisitive and enthusiastic students, I’m feeling cautiously hopeful. But, that hope diminishes unless we are all able to break through current patterns of resource consumption and population growth, and begin to work more collectively to honestly address how our behaviors impact the Earth and all its inhabitants.

Dear Climate (U Chaudhuri, F Ertl, O Kellhammer, M Zurkow), General Assembly, 2018. Circle of nylon printed banners on wood poles, 12 ft. high, 84 ft. diam.; each flag 60 x 36 in. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson.

Dear Climate is a creative research collective that was founded in 2014 by Una Chaudhuri, Fritz Earth, Oliver Kellhammer, and Marina Zurkow. Their installation “General Assembly” consists of 20 flags in dialogue with one another; the black flags present problems and the white flags offer solutions. It was inspired by the notion of a cross-species “United Nations,” which would join humans with flora and fauna, and bring all of Earth’s inhabitants and forces onto a level playing field. Dear Climate suggests that humans broaden their worldviews to not center on their own species, because everything that exists on Earth has an equal stake in its future. Acknowledging that in itself is a step towards a solution.

What’s next?

David Brooks: I’ve spent the last three years working specifically on projects that focus on how we simply perceive our environments. The intimidating scale of consequences one might weigh in their daily life challenges our conventional perceptual skill-sets. I believe this is the one of the places we require a great deal of evolution and sophistication, and it will most likely be accomplished through the arts.

Marina Zurkow, Dear Climate: Food as art and interface for change.

Una Chaudhuri, Dear Climate: Spread multi-species consciousness.

Oliver Kellhammer, Dear Climate: For the planet? I shudder to think about it, but I do, a lot. As for me, I am continuing my research into the emerging ecosystems of the Anthropocene.

Gabriela Salazar: We need to support renewable energy from wind, sun, and water, and demand that our elected officials stop kowtowing to industry and fossil fuel money. We need to demand that subsidies and money go into technologies that already exist to get us off carbon-intensive activities. And we need to think deeply and critically about consumer culture.

Hara Woltz: I’m working on a series of pieces based on phenology and the impacts of climate change on the timing of biological phenomena. I’m also wrapping up a collaborative project on biocultural resilience in the Solomon Islands.

David Brooks, Permanent Field Observations, 2018. Bronze, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson.

Will you offer us a piece of actionable advice?

David Brooks: Pay attention to the details around you. The big things are connected to the little things, even if it feels like a drop in the bucket. It has to start with an actionable sense of responsibility with the things around you.

Find any way possible to forge this sense of urgency in a positive light, not one that is simply about prohibitive mandates.

Marina Zurkow, Dear Climate: Practice conscious, flexible, communitarian choices; love ecospherically as an earthling among many species; and become materially aware that you live in an ecosystem.

Una Chaudhuri, Dear Climate: See everything through a multi-species and geo-centric lens.

Oliver Kellhammer, Dear Climate: Be kind to all sentient beings! You might be reborn as a slime mold and that will be great!

Gabriela Salazar: Vote and demand change. And take a sober look at how you contribute to the problem, and what you can do.

Gabriela Salazar, Matters in Shelter (and Place, Puerto Rico), 2018. Coffee clay (used coffee grounds, flour, salt), concrete block, wood, and polypropylene mesh tarp, 12 x 16 x 20 ft. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jerry L. Thompson.

“Indicators: Artists On Climate Change” is on view at Storm King Art Center in Cornwall, New York through November 11, 2018.

Haley Weiss (@haleyfweiss) is the deputy editor of Newest York. She lives in Brooklyn and still wishes she had a dog. Her former foster pup Dutch now lives happily in New Jersey.