Ted Dodson is the author of “At the National Monument / Always Today” (Pioneer Works, 2016) and “Pop! in Spring” (Diez, 2013). He works for BOMB and is a former editor of The Poetry Project Newsletter.

Read MoreTwo Poems by Ted Dodson

Ted Dodson is the author of “At the National Monument / Always Today” (Pioneer Works, 2016) and “Pop! in Spring” (Diez, 2013). He works for BOMB and is a former editor of The Poetry Project Newsletter.

Read More

In the far corner of the gallery, she watches him lurch forward, and then back, like a boxer, as if each new pass brings him closer to revelation. He reads the small placard with the title of her sculpture. Tufts of grey hair protrude above his ears, crowning a bald spot marred with eczema. Professor Lautrec is an old, unkempt man, and still, she is flattered by his attention.

The space is quiet except for the stamping of his boots, chalky half-moons left behind on the wood. She shouldn’t be there. Her dealer discouraged it, said it countered the image of the artist as recluse. But she has always been her own best salesman. Instead of picking up her daughter from school, she has been lurking in the gallery on weekday afternoons under the pretext of signing some papers. And now, there’s Professor Lautrec.

“Jan-ette,” he says, turning to face her. “That one.” He gestures towards the piece before him, an ice blue acrylic trumpet, submerged in a nest of frayed twine. “That’s the one.”

She had sliced her fingers up during its assembly, nearly burned down her studio in aggravation.

“It’s sold,” she says.

He takes her hand in his and squeezes. “A shame.”

She walks with him to a café on 10th Avenue, a small French place where he knows the owner. He orders a bottle of Chenin Blanc. Despite the March chill, they sit at a table outside so he can smoke. When he offers her a drag, she waves her hand, and then accepts it anyway. He talks about the scene, who is on the up, who has gone insane and fled to an organic farm in Michigan.

“I never thought you had the temperament for sculpture,” he says. “But here you still are.”

The pleasant scent of sautéing garlic wafts from inside the cafe. A woman in a boiled wool coat pushes a stroller down the sidewalk. Janet smoothes her hair and pulls it over one shoulder. Marc Lautrec. What if she had chosen a man like that. Someone worldly, without illusions. She and Rick have built an enviable life, but he thinks he won a prize in marrying her. To live up to that ideal, even to think about it now, exhausts her, makes her feel like she’s given up some deep part of herself to please him.

“Here I am,” she says, and takes her own cigarette from the pack.

+

A decade earlier, at a more prestigious gallery, Professor Lautrec invited her to the opening of a Czech sculptor’s first New York show. While they drank Chardonnay from plastic cups, Professor Lautrec introduced her to his friends, dealers with embossed business cards representing artists who did their MFAs at Columbia and Yale, and not the second-tier school Janet was attending.

You’re the whole package, he whispered to her, his palm on her ass. She’s the whole package, he told the dealers, patting her.

He led her towards a strange, electrode caterpillar at the center of the gallery.

I’ve been dying to show you this piece, he said. What do you think? Wait, don’t answer yet. Take a lap first. Think about scale.

She laughed, but he looked at her intently, and so she walked the perimeter. Around her, the other people mingled, women wearing large earrings and bright lipstick, men with angular haircuts.

Now, he said, smiling, tell me.

She felt the world open up.

While collecting their coats, they ran into Carole Whipps, a visiting artist Janet had been studying with. Carole kissed Janet on both cheeks and then guided her away by the elbow. She had the most beautiful white hair, thick and luminous, two columns of light. Janet asked her what she thought of the show. Carole put her hand on Janet’s arm and told her to be mindful with Professor Lautrec.

This surprised her. Carole was not the first older woman to warn her off, but Janet had simply assumed they were jealous. What could be greater proof of Janet’s own genius than an affair with an ugly, brilliant man?

Janet nodded, but it felt too late. She had already made her plans.

When she mentioned the exchange to him in bed that night, he looked thoughtful. Women her age don’t have an easy time, he said.

Some weeks later, just before her twenty-second birthday, Professor Lautrec summoned her to his apartment. He had the flu. “Bring some Campbell’s,” he instructed.

But Janet was a woman who created things, and although she had never followed a recipe in her life, that morning she drew from the same well of care and precision she would a new piece rendered in copper, paraffin, or plaster: two medium-sized carrots, the most symmetrical and vibrant of the bunch. Three celery stalks scrubbed clean. Sweet, blinding Vidalia onion. She diced them all and swept them from the cutting board into her mother’s red Le Creuset. She added dark meat and left the pot to simmer.

Hours later, while it cooled, she smudged her eyes with black pencil and pinched her cheeks, and then stepped into a pair of good underwear.

On the subway from Queens to Brooklyn, the heavy pot warmed her arm like a newborn.

“Sorry about that,” she said, clutching the Le Creuset in his living room. Cold liquid dribbled now down the sides, and as she lifted the cast iron lid, a gamey, sulfuric odor escaped. She stared at the bloated stars of chicken fat.

“Not everything must be aesthetic,” he said.

He untied his bathrobe and pulled her into his lap. His skin was a damp sheet.

“You’re sick,” she protested.

“You’re making me better,” he said, and with a quick motion hooked his thumbs under the waistband of her wool tights. They bunched at her knees and her bare ass bumped against the tops of his thighs. She clutched the arms of the chair for balance. Over his shoulder she noticed a canvas propped against the wall, a still life.

“What’s that?” she asked.

“I’m holding on to it for a Danish friend of mine. He’s in a group show next month.”

“It’s evocative,” she said.

He collected her hair in his hands and kissed her neck. “Beautiful girl,” he said. His face burned with fever. His beard felt oily. This had always been her problem: she was a girl who ignored instinct.

She was wet before he told her so. As he carried her to his bedroom, she looked back at the painting and wondered what Carole would think about the way the light hit the fruits in the clay bowl.

His bedroom was windowless, separated from the living room by a mauve curtain. The sheets were soft, a high thread count. She’d never touched sheets like those before. As he moved over her, his form blocked the glow from the ceiling fan.

Wanting to please him, she pressed her lips against his ear and whispered the dirtiest thing she could think of.

Abruptly, he cried out, and collapsed into her neck. He dug his nails into the sharp concave of her hip bones. “Darling,” he said.

She had one rule in all this. A rule he had always followed since she was not on the pill, and he said he found condoms degrading.

“Did you—?”

“I am only a man,” he said, and then rolled off her and began to snore.

The bathroom smelled like amber and pine. She waddled to the toilet with a tissue between her legs, sat down, and closed her eyes. When she opened them, she was looking at his prized sculpture, the piece he’d lectured about. The one piece he would never sell. How easily we give up our best work to make a buck, he often said. It was a worn-out sneaker rendered in creamy marble, the size of a loaf of supermarket bread. It sat mounted on a pedestal beside the mosaic shower.

Janet imagined a parade of women sitting in her place, a hundred manicured feet plying the soft bath mat, staring at his masterpiece. Carole, with her callused hands, her singular vision, would never dirty herself in this way. But Janet didn’t flee contamination. She barreled towards it.

Abruptly, she leapt forward and whacked her right hand against the marble sneaker with her full strength. The pain was instant, numbing, spiraling deep into her bone. She gasped and pressed her hand to her stomach.

Her legs trembled as she ransacked the medicine cabinet for some kind of weapon. A men’s razor. She inhaled sharply, and then dragged the blade across the marble. It barely marred the surface.

Her bladder pinched.

Cold and naked, she put one foot on the side of the tub and the other against the wall, perched over the sculpture. Eyes closed, she bore down. Piss fell and collected in the crevices of the marble.

She found her clothes in the living room and put her tights back on.

He stirred and called her to him.

“I’m practically cured,” he said. He propped himself up on his elbows. “Do I tell you enough how stunning you are?” He took a lock of her hair between his fingers. “You’re the kind of girl men will line up to marry.”

She put on her shoes.

+

Professor Lautrec flags the waiter to bring them the food menu and then rests his hand on Janet’s wrist. “Tell me, how is Françoise? I haven’t spoken to her in forever.”

In the end, desperate for a leg up, she had called one of the agents with the embossed cards, Françoise Smart, who took her out to lunch and then stuck with her, for eight years now, through the birth of her child and those first tortuous months where Janet never made it to her studio, when she was waking up every hour in the night, convinced her daughter had stopped breathing, pressing her compact mirror beneath her rosebud nose.

“Françoise is Françoise,” Janet says vaguely.

“I was so glad I could make the connection,” he says.

“What happened to the shoe?”

“Pardon?”

“The sneaker,” she says. “The marble sneaker.”

He leans back in the chair, and squints at her. “Oh, that thing.” He laughs. “I sold it.”

She hasn’t smoked in years, and now her throat is burning. Still, she inhales.

He shrugs. “Someone offered a good price.”

Isabella Moschen Storey is a writer and editor. Her work has appeared in Joyland, The New York Times, and City Limits Magazine. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and their two plants.

On Thanksgiving Day, photographer Lucia Buricelli made a list of everything she could think of related to Christmas trees. For a week, she walked from 14th Street and First Avenue up to Midtown and back each day, taking pictures of people selling trees in the middle of busy sidewalks. She visited a Christmas tree farm upstate, where she found an unexpected Santa Claus posing for pictures with children who had been dragged along by their parents. She went to Soho Trees in Manhattan, a place that sells real trees, and to Christmas stores in Little Italy and on Seventh Avenue. “The huge amount of completely useless stuff reminded me,” she says, “that there are moments when it is nice to take a break.”

Lucia Buricelli is a photographer and photo editor from Venice, Italy working in New York City. Her work on puppetry was recently featured in Newest York.

Photos: Victor Llorente

For our inaugural Local Spotlight, a series profiling artists working in varied fields and New York City neighborhoods, we sat down with actor and 21-year-old Washington Heights resident Jaime Arciniegas, who you may recognize from the pre-film Coca-Cola commercial at Regal Cinemas over the past year.

How did you get into acting?

I started acting when I was seventeen. It was a curiosity of mine after I had been tormented at school for a while. It was an escape from reality. You know, bullies. Kids are just mean for any reason. Because of my background — I had been born in Colombia, and moved to Texas, and then once again back to Colombia — kids didn't actually see me as their peer. They saw me as a foreigner, an outsider. I had lived in Texas for such a long time. All of these people who were trying to speak a second language had an accent, but I didn't. I think they always felt that I thought I was better than them just because I could speak English better.

I saw an escape through acting. I was in love with the idea of it — with the idea of not being me. I was going to become a geologist. I was going to study rocks for a living, because at the time I used to think that money equaled happiness. But I was just enthralled by this idea of pretending to be so many other people. At the same time it was an excuse to not be me, to not be myself, to not live the life that I was living. I believe acting is the truest form of storytelling — these characters, whether they're based on fiction or reality, in that moment, that's the truth. And nobody can deny it.

How much do you bring your own experiences to bear in your work?

The methods I learned in school were based off sense memory, experiences, and imagination. When I tackle a role, I try to do as much sense memory as possible. When I did Rabbithole for City Island Theater Group up in the Bronx, the character I played was a troubled teen who accidentally kills a child in a car accident. Obviously that's not something — I haven't done that before. But that's where imagination comes in play, where we try to connect the dots of something similar, and try to fathom what that feeling would be. We have the play in front of us. We read it, we understand it, we can take what the playwright is trying to tell us about this character. Beyond that, it's up to us to create the backstory, the foreground, the personality.

The first acting class I ever took in Colombia was with a bunch of children, which was only because I had made a mistake. It was the wrong class: it wasn't the adult's acting class, but I was seventeen so I could fit in to the children class. Kids, I think, are the best actors. Everything is real to them. Watching that and learning from them actually helped me in the future with things I came to do. You can tell them as much as you want what something is, but if they don't believe it, it won't be. Whatever they believe, that's their own truth. That's the power of what this craft is.

What New York has offered you as an environment to develop your practice?

Coming to New York was the best decision I ever made. After graduating, I found that there's this really vast pool of all these acting networks. There are so many opportunities that people overlook. They think Hollywood is the only place where you can do film or TV, but New York shoots so many pilots each year, so many movies come here all the time. It's beautiful to depict on camera. Obviously on stage we have Broadway, Off-Broadway, but there are also all these local makeshift theaters that produce plays 24/7, all the time, every week. Nearly every neighborhood you go, there's at least one place to go see theater, or one place to be a part of that experience. As an actor, it's been like another year of school — in school, you're in one building just rehearsing and performing on their stage. In the city, the whole city's your rehearsal space, and you've got to find what theater wants you to perform, and you've got to audition to keep going.

We're very excited to announce the forthcoming publication of Ben Fama’s second book of poems, Deathwish, by Newest York Arts Press in Spring 2019. ☠️

Read an excerpt of the forthcoming work published in our Staycation issue here.

Ben Fama is the author of Fantasy (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015) and his work has been featured by BOMB magazine and New York Tyrant. He lives in NYC.

Purchase previous releases by Newest York here.

Sea Wall: Photos on Climate from Newest York

August 28 – September 11, 2018

Opening August 28, 7-9 PM

Photo: Lidiya Kan

In celebration of Newest York’s twentieth issue Sea Wall, XXXI Gallery and Newest York are pleased to announce an exhibition of contemporary photographs from the arts magazine’s archive across New York’s five boroughs exploring the themes of water, climate, beaches, and islands.

The exhibition was organized by Luiza Dale, creative director of Newest York, and curated by Jonno Rattman, visuals editor at Newest York.

Photographers featured in the exhibition include:

Maureen Drennan is a photographer born and based in New York City. Her work has been included in exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, the Tacoma Art Museum, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, and Aperture, among others. Her images have been featured in publications including The New Yorker, The New York Times, and California Sunday Magazine. She currently teaches at LaGuardia Community College and the International Center for Photography in New York City.

Lidiya Kan is a documentary photographer and a filmmaker based in New York. She currently teaches photography at LaGuardia Community College.

Victor Llorente is a 22-year-old photographer from Madrid, Spain based in Brooklyn and is currently a senior at the Fashion Institute of Technology. He is a member of the New York City Street Photography Collective and his work has appeared in the New York Times.

Julian Master is a photographer from Eugene, Oregon currently living in New York City. His work confronts the relationships between cities, commercialization, globalization, and the age-old theme of weirdness. Not formally educated in photography, Julian derives inspiration from placing himself in unfamiliar crowds, traveling abroad, and dealing with extreme weather.

William Mebane works as a photographer on editorial, fine-art, and commercial projects. He is a contributor to The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek and The Paris Review. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, Martha, and their two sons.

Adam Pape is a photographer based in New York City and he continues to draw from the city for his subjects, from its nocturnal labor to its native wildlife. He earned his MFA from Yale in 2016 and his work has appeared in several publications including The New Yorker Magazine and The Fader. His photographs from Inwood and Washington Heights will be published in his upcoming monograph Dyckman Haze with MACK Books.

Emily Pederson is a photographer and filmmaker based in NYC. Originally from Rhode Island, she focuses on human rights and has made in-depth projects on social movements and the impact of the Drug War in Mexico. Her documentary work has been supported by Field of Vision and published in The New York Times, The Atlantic, La Jornada and El Faro.

Natalee Ranii-Dropcho is an analog photographer and real-life storyteller based in Brooklyn.

Jonah Rosenberg is a Brooklyn-based photographer who likes making work for himself and for others. His clients include Popular Mechanics, Herman Miller, Runner's World, Fast Company, Inc., W Magazine, Stereogum and others.

Daniel Shapiro is a freelance photographer from Cleveland, Ohio now living in Brooklyn, New York. He has shot work for Lufthansa USA, New York Fashion Week, Berkshire Hathaway, and Dia Art Foundation. Daniel has been featured in Noisey, CFDA, Aftenposten Junior, and Malibu Magazine.

Jacqueline Silberbush is an artist who lives and works in New York. Her work has been shown in the Jewish Museum, TANG Museum, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, featured on NPR’s Brian Lehrer Show with Bruce Davidson, and portfolios of her work have appeared in PDN, VICE, National Geographic and several others.

XXXI is a storefront gallery and project space run by XXIX.

Newest York is a project of Newest York Arts Press, a 501(c)3 not-for-profit publisher and arts organization. Our mission is to support and showcase local artists whose work engages with New York City.

Photo: Maureen Drennan

It is easy to forget that New York City’s waterways are very much alive—living, breathing habitats that ebb and flow based on our behavior as their natural stewards. Industrialization didn’t help: for over a century, factory-lined waterfronts coupled with sub-par environmental practices decimated entire ecosystems that long called the rivers and bays home. But due to a concerted effort amongst local officials and advocates, New York’s waters are cleaner than they’ve been in decades, ushering in a new (or old) era of marine wildlife here.

George Jackman, PhD, is one of those reasons why. A retired N.Y.P.D. officer-turned aquatic ecologist, Jackman is now a habitat restoration manager with Riverkeeper, an environmental organization that focuses on the Hudson River. The key waterway has recently seen whales and other fish communities return to its shores, thanks in large part to improving quality, and hard-fought conservation work. Yet while there has been a number of successes, Jackman says, there’s still a long way to go.

I know that you used to be a NYPD officer. How did you change from police to ecologist?

George Jackman: I tell everyone that I left the NYPD because I wanted to make a difference in my life. I say that somewhat tongue in cheek, somewhat facetiously. I started out with a high school education, and then the NYPD. Then I started riding horses, and I always had an abiding love for animals, and for the environment; I was a hunter and a fisherman and I just needed to know more.

I got kind of disenchanted with the politics as I got higher in the police department. When I started working for a living, I started realizing, "Wow, you’re nothing without an education." I felt something was missing. So I went back to school and realized, "Holy cow, if I study, I can do anything I want!" So I took five semesters of calculus right away and four semesters of physics. Then I decided to be a wildlife biologist. So I started studying aquatic ecology at Queens College. I went to grad school, and I just loved what I was doing. I entered a PhD program, and I’ve never looked back…. One thing led to another and I was up in the tundra working on polar bears and geese. It’s what I’ve always wanted to do.

How does the current debate in Washington over environmental policy impact your work?

I thought being a NYPD cop was sad, but being an ecologist is sadder. What I see happening to the world, I wish I didn’t know. The Endangered Species Act, the Magnuson-Stevens Act under threat—I want to cry. The way we’re treating this planet, I want to cry. Man’s inhumanity toward man is brutal, but man’s inhumanity toward environment and other organisms is appalling. I wish I could just stick my head in the sand. It’s like once you take the pill and see the matrix, you can never go back. I wish I could go back in some ways.

That’s how I got to be where I am. Some of those transcendentalists were my inspiration. Walt Whitman said, "I want to wrap the world around me." That rapture he discusses—I’ve always had that feeling. I grew up in a dysfunctional home, and that was my only solace. The only stability in my life was nature. I wish I could make it my god but you can’t do that. That’s where I am.

Let’s talk New York. People don’t imagine there’s a lot of ecology going on in Manhattan and the other boroughs. So what do you say to them?

There’s life everywhere on this planet. I try to tell people, I don’t care where you are, you gotta look around. When I was on patrol in Bushwick back in the day—when it was still a rough place—I would look up and see solace and inspiration in the merlins and peregrine falcons attacking pigeons. It would give me inspiration at times, in cemeteries and other places. Then I started doing urban ecology working on the Bronx River. I caught the first herring and the first eel in the Bronx River. I was the first to attempt a fish passage in New York City.

In New York City parks, there’s life. But I had to go look for it. The oldest tree in New York City is 450 years old. Life is everywhere, but you have to find it. Anybody can do ecology in rural places, but its urban places… that’s a challenge. As we encroach on nature more and more, we’re going to need to find ways to live more in harmony with nature, not in dominion.

How have you seen New York’s ecology change over the past few decades you’ve been working at Riverkeeper?

You know, it depends. Hey, we’ve got coyotes in New York City... coyotes are cool! They are America’s only endemic dog. It’s really cool. Some people hate them—I find them inspiring! They represent a wildness. There are deer in New York City, and turkey, too. I remember riding my horse in Pelham Bay Park with a wild turkey next to me. I said to myself, "My god, if I shot this thing I’d be the first person to shoot a wild turkey off the back of a horse in New York City since the 1600s." Of course I didn’t, though.

Ecology in New York City, it’s different. The winter flounder are gone, the quahog clams are gone. Where I used to fish, swim and hunt—they’re all million dollar houses now. So much has changed. But the ecology—it’s almost like the movie Trading Places. Some fish have left, but some new fish have come in. New York is an incredible location. It’s the northern zone for southern species and the southern zone for the northern species. It’s this critical junction, so it’s a richly diverse area. I like that analogy to Trading Places. I think it’s hard for us to grasp sometimes that things are just different.

Can you talk a little bit about why the ecology might look different, in terms of legislation or policy?

What has changed in the city is that there’s a lot of grassroots efforts now. People are interested in ecology. New York has attracted a lot of young, educated people from all over country, and world. It has brought an awareness that we didn’t have. There was a time when New York City was considered the ‘rotten apple.’ Now it’s just the ‘Big Apple.’ There was an oil spill in Greenpoint from ExxonMobil, but now they’re being forced to clean it up. GE forced to clean up the Hudson River. Riverkeeper, a tiny environmental organization, sued a nuclear power plant, and we won! That power plant killed a billion fish a year.

So what’s changing? A lot has changed. You know, social media helps change this, too, because now we can galvanize a movement. The river’s getting cleaner in a lot of ways but we’ve still got a long way to go. We lost the rainbow smelt. That’s climate change. Winter flounder are on the way out—that’s death by a thousand cuts. Usually it’s never one incident… it’s a variety of assaults on species.

If you could talk to people in New York City who aren’t really that interested in the environment, what would you tell them to do to help?

Do anything! I don’t care—pick up a plastic bag! Where do you think that thing’s going to end up? In some loggerhead turtle’s mouth. What’s the answer? Become aware. Don’t be a sleepwalker. I see so many people just watching sports—it’s not bad, but there’s more in life. You gotta do something. Sometimes I feel like the Lorax. When, at the end, they say, "Nothing will change unless..." Unless what? Unless somebody like you really, really cares. It becomes a way of life. I don’t know how you become that, but you gotta do something.

So it’s a complex answer. Are things getting better? Yeah. Is there more work to do? Yeah. Our message and our mission is even more important. As species decline, we got more work to do. I don’t care what other people are doing, I know what I have to do. Treat the river like it’s a soul. It’s a beautiful river.

A former New York City resident, Melissa Cronin is a marine ecologist and writer living in California and currently pursuing her PhD at UC Santa Cruz. Her writing has appeared in Grist, Slate, Salon, The Nation, and elsewhere.

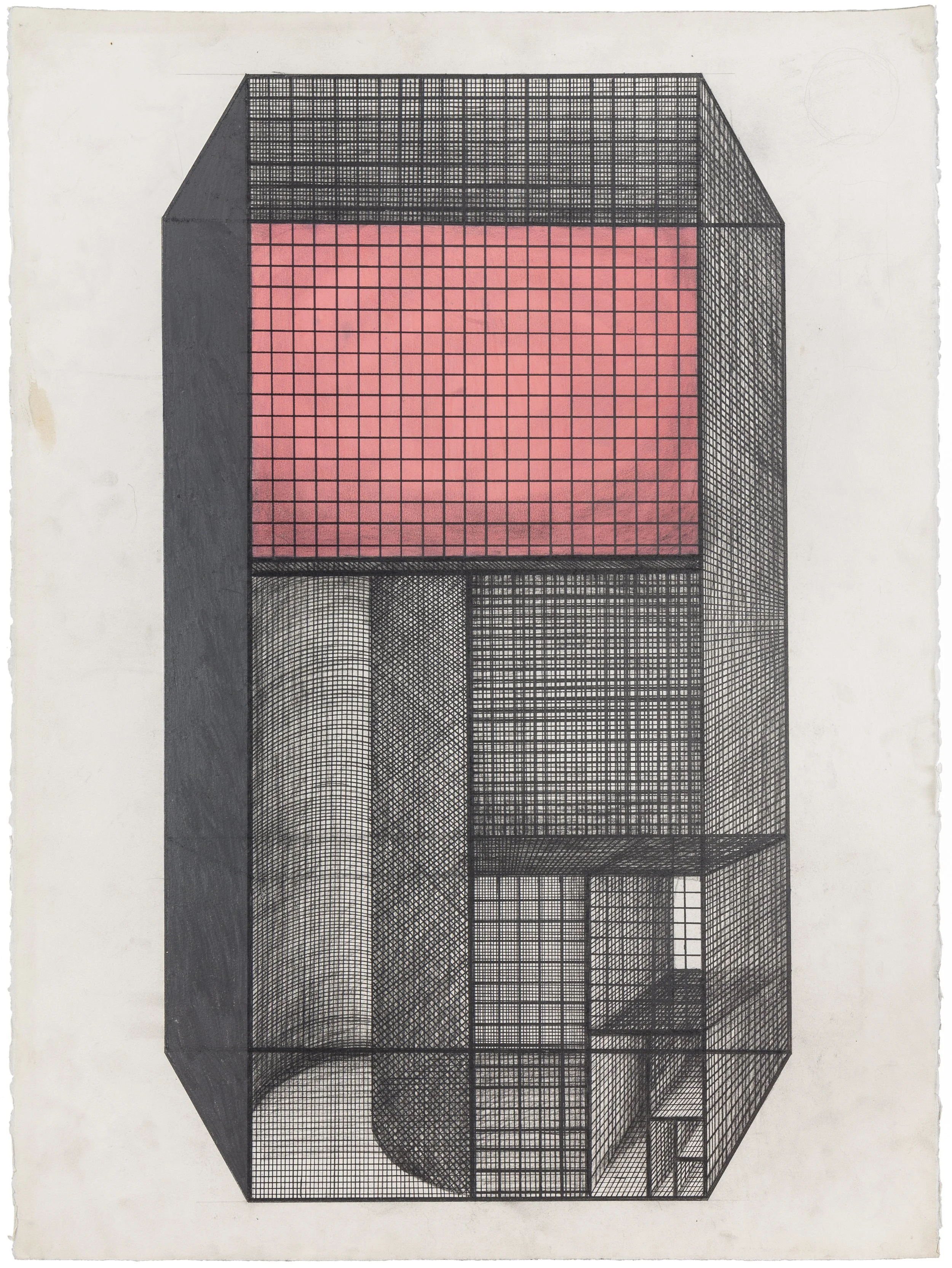

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Drawing for ‘Container of Perceiving,’ 1984. Acrylic, watercolor, and graphite on paper, 42 1/2 x 72 3/4 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

"This mortality thing is bad news," declared Madeline Gins, the poet and philosopher, to the New York Times in 2010. It’s a bold statement, and Gins offered it for the obituary of her husband, the artist Arakawa. Together they spent decades collaborating on mind-bending architectural projects. Their spatial experiments, both speculative and realized (which Gins continued until her own passing in 2014), sought to oppose death in alignment with a concept of their own invention: “reversible destiny.”

According to Irene Sunwoo and Tiffany Lambert, the curators of a new show of Arakawa and Gins’ work – “Arakawa and Madeline Gins: Eternal Gradient” – reversible destiny is as surreal as it sounds. It can be defined most simply as “arguing for the transformative capacity of architecture to empower humans to resist their own deaths.” The exhibition, which opens today at Columbia GSAPP’s Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery, features previously unpublished material with a focus on the duo’s preparatory hand drawings from the '80s. Sunwoo explains that this is a time when Arakawa and Gins’ “energies converged in the realm of architecture.” While the works included seem to exist in a sci-fi universe of their own, the logic of that world is somehow sound; Arakawa and Gins were both interested in the body and biology, how people move through and perceive space, and these creations seem to say don’t be too comfortable, get knocked off-kilter, and see your surroundings afresh. (In the case of the duo’s later works that came to physical fruition, like this public park in Japan, you might literally get knocked off of your feet.)

Is there anything to this idea of reversible destiny? Can the very walls around you stall your inevitable demise? We recently spoke to Sunwoo, who’s an architectural historian, and came away with three points of departure for Newest York readers – an introductory guide to reversible destiny, if you will. We invite you to start here with the knowledge that there’s much more to explore, even within this precise slice of Arakawa and Gins’ body of work.

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Study for ‘Critical Holder,’ 1990. Acrylic, graphite, and color pencil on paper, 42 1/2 x 61 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

"It's possible to imagine a new relationship between the body and architectural space other than what we have been accustomed to for centuries or millennia," Sunwoo says. "By creating those new relationships and experiences, we have the potential to have different psychological, perceptual, biological, and emotional responses and experiences, which could totally change the direction of our lives – our mortality in that sense. It's not a biological process where time is reversed – it's not a Benjamin Button situation – it's much more conceptual than that, and spiritual I would say as well. But I think the important takeaway is that there is this belief that there is a different type of life possible and that architectural space can somehow make that realized."

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Screen-Valve, 1985-87. Graphite and acrylic on paper, 30 x 22 1/2 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

"I think [play] was always central [to Arakawa and Gins’ work], even looking back at their paintings and poetry. A lot of Arakawa’s paintings are these puzzles or mind games, using language and stripped-down imagery; it wasn't pictorial necessarily, but these visual and semiotic puzzles. And then with Madeline's writing – and I'm by no means an expert on the literary side of things – it’s in the layout of some of her poems, the way that punctuation is used. For example, I found a letter where she as apologizing to someone for the delay in getting back to them and she had spelled out delay with a 'D' and several hyphens, an 'E' and several hyphens, an 'L' and several hyphens, and so on and so forth. So in images and language, play was always there. In spaces it's happened as well, because there's a delight that happens when you are thrown off balance just a little bit; it's this element of surprise that I think goes back to the concept of reversible destiny to use triggers that make you see your environment and yourself in different ways. [In my experience of their physical works,] your body really is forced to function in a different way, so much so that sometimes you have to grip onto the walls to keep yourself from falling down. Your body is constantly active, and your mind too – that was part of the intent, I think.”

Arakawa and Madeline Gins, Perspectival view showing entrance to ‘Bridge of Reversible Destiny,’ 1989. Graphite and collage on vellum, 24 x 30 in. © 2018 Estate of Madeline Gins. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Madeline Gins. Photo: Nicholas Knight. Courtesy of Columbia GSAPP.

“The essence of [reversible destiny is] a sense of empowerment over your own state of being in the world and understanding all of your intellectual, physical, psychological, and social capacities – and to shake things up so that life doesn't seem like a one-way path. It's much more dimensional than that and can go in any direction possible; that was the message that I was getting from it, and I would subscribe to that. It is really so centered on the individual and the body and its own capacity, rather than just accepting all of your surroundings and conditions. I think it's a call to wake people up."

“Arakawa and Madeline Gins: Eternal Gradient” is on view at Columbia GSAPP’s Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery from March 30, 2018 through June 16, 2018.

Earlier this month, photographer Victor Llorente (@victor.llorente) snapped this year's hottest Purim looks.

In our first post of this month's miniblog for our 16th issue BODIES, photographer Chris Lee attends the Chinatown Lunar New Year parade and festival.

I don’t remember how I found her, or what mysterious force led me into this corner of YouTube, but I do remember the first etiquette video of Gloria Starr’s that I watched. It was about afternoon tea. The video begins with Starr seated before a cluttered dining table—in front of her is an array of teapots and cups in varying shapes and sizes. To her left, filling half the screen, is an absurdly large floral arrangement. Starr, wearing a black dress bedazzled with gold and silver beads, stiffly addresses the camera: “Gloria Starr here. Our session today is on afternoon tea. I set out a beautiful display, and in preparation for a lovely party, I’m wearing a goddess gown from my adventures in other cultures.”

Starr, as I would later come to learn, describes herself as an “international etiquette, manners, and social graces coach.” According to her website, she has worked with members of royal families and Fortune 500 companies across the globe for over three decades. On her YouTube channel—a virtual finishing school of sorts—she posts homemade lessons on all matters of etiquette and presentation. There are hundreds of them, each more surreal than the last: Gloria Starr on how to eat pasta; Gloria Star on how to accessorize; Gloria Starr on how to pay a compliment. Some videos are humorous, such as the one on grocery store etiquette. Others are quite spooky, such as this one, in which she sits in a low-lit room before a ghostly candle-lit dinnerscape, explaining the intricacies of a formal table setting. After watching a few Starr videos in succession, the lo-fi production values, the cool intonation of her voice, and her gentle, if confusing, decrees (“When you use your napkin, it’s dab dab, never rub rub”) take on an almost hypnotic quality. But despite her occasionally, well, wack (and often outmoded) advice, Starr’s ultimate message is aspirational in nature: it is about being the best version of yourself. She believes in the promise of each of us. “You are a living, human treasure,” one video begins. Words to live by!

By way of introduction, below are five videos I thought might be particularly relevant to the Newest York miniblog reader. Enjoy?

We spend a lot of time doing both of these things in New York. In this video, Starr explains how to handle both gracefully. Men: NO walking with your hands in your pockets.

Very relatable for many of us office-goers. In this video, Starr instructs on how to “maintain your dignity” in the workplace. Big takeaways: bring minimal (if any) personal objects into the office, no personal phone calls, and NO loud talking.

A lot of people in New York would do well to watch this video. Starr believes in raising your hand to your mouth when speaking on the phone in public, that way your words stay only between you and your caller.

New Yorkers love to network. Here, Starr instructs on the proper way to give and receive business cards. The most important takeaway: NEVER put a business card that’s just been handed to you in your pocket or bag while the person is still in front of you. Hold it in one hand until you part ways.

No matter what you’re walking into—be it the club or the boardroom—it should be an opportunity to make a memorable first impression. Starr recommends pausing for impact.

It’s my final blog post of the month and I’m writing about the final episode of Blossom. I hope that isn’t too on the nose. Season 5, Episode 22, Goodbye.

The series begins and ends with Blossom’s video diaries. The conceit of Blossom’s video diary crops up regularly throughout the five seasons culminating in this last episode of Blossom, a show creator’s wet dream. Demonstrating perfect foresight, the video diary trope is so executed so well that they can cut right to the first episode and show us, in the same frame, young Blossom. Even Holden Caulfield is mentioned in her final speech. You may remember from my first review that HC was the initial inspiration for the character of Blossom, originally conceived as a young man.

The meat of this episode is centered on some drama surrounding Blossom’s dad Nick’s desire to sell the house. At this point, her brother Joey is engaged, Nick is seriously involved with a new woman (and they’re pregnant!), and her brother Anthony has started a life of his own. (Also, her best friend Six is now hot and working at a fried chicken restaurant.) It’s only Blossom who isn’t quite ready for change. She’s going to be starting college in 1-2 years, according to what they say in this episode, which makes this whole plot line feel very much in service of closure for the series. Why wouldn’t Nick just wait?

The scene where Nick tells Blossom that he is going to sell the house is highly choreographed. He delivers the news, feigns beginning to butter his toast, and then gets up to grab the salt and pepper shakers from the bar. Blossom then stands too, facing him. Why? Why must you sell the house? A bigger question is, Who? Who reveals something like that to their sentimental teen daughter and expects that they’ll be excited about it, as Nick does?

When her father suggests that selling the house will be a clean break with their old memories, Blossom retorts, “This isn’t a break, it’s an amputation.” And that isn’t the only amputation we witness in the span of this episode. The episode ends with what we presume is Blossom’s last video. In it we see another amputation, the separation of Blossom and Mayim.

As Blossom talks about the lessons she learned along the way, the timeline becomes a point of inquiry. When we first met Blossom, she’d experienced no event that would precipitate her video journal. And the move doesn’t demand an end to Blossom’s video diary. The timeline here, again, is transparently in service of the show, so much so that it borders on breaking the fourth wall. The question becomes: are these reflections about Blossom’s life, or are they more like Mayim’s reflections on her experience with the show?

The lessons learned are, without further ado:

I’ve mourned the loss of some inconsequential internet ephemera this month. Sweet things, curiously hollow ones, and all without a doubt insignificant. No matter how insignificant, I can’t help but feel sad when I discover that content I’d expected would last forever has passed on. Even if I know that much of it was designed to last for only a short while, the feeling persists. Yet for every deleted tweet and Vine that I wish was still accessible, there is a Snapchat that I wish had disappeared as intended. This brings me to my final point of this month and maybe ever—if Snapchat is supposed to be about living in the moment, why can I still watch DJ Khaled lost at sea?

On December 14th, 2015, months into his motivational, unofficial Snapchat residency, music producer and radio personality DJ Khaled jet skied to Rick Ross’s house in the afternoon and then got lost in the water in the dark of night with only his phone flash and unflappable demeanor to guide him. Despite his precarious situation, he documented the trip on Snapchat in impressively earnest detail, captioning each snap with the pray emoji, an inspirational message, or a genuine plea for someone who knows him to call his partner Zay Zee and tell her he was lost at sea on his jet ski. More than two years later, you can watch the whole thing on Youtube, although, to be perfectly clear, I think that is wrong.

Vine is (was!) an app that you could put six-second videos on for what I imagined would be forever. In the days since its demise (January 17, 2017), Vine’s website has become a supposedly searchable archive of Vines, but I’ve tried and failed to find a specific Vine at least… two times, which seems like the appropriate number of times to try such a thing before abandoning my efforts completely. This is all to say, call me crazy, but sometimes YouTube is the best way to watch a Vine. YouTube, however, is a stupid way to watch a Snap. Snapchat’s whole reason for existing (for now!), I thought, was as a platform where you can broadcast photos and videos just once, or for up to 24 hours if it’s a Story. “Delete is our default 👻” it says on the Snapchat support page, which I like to think is a place to find the truth. So I don’t think we should be allowed to watch Snaps in perpetuity on Youtube.

If you search the stunning combination of words “Kylie Jenner snapchat instagram” you will find a Kylie Jenner Snapchat Instagram account (duh!) that posits to be “the #1 source of ALL Kylie Jenner Snapchats [sic] and MORE! 👑” which I find bizarre because wouldn’t Kylie Jenner’s Snapchat be the number one source of all Kylie Jenner Snaps? As an avid user of Instagram stories, a direct descendant-slash-rip-off of Snapchat where videos live for only 24 hours in your Instagram feed, I find that I don’t want my stories to live on forever without my consent. The fleetingness gives me freedom to be more unhinged than I might be in a permanent post, to ask for help whether it’s genuine or in jest. If I was lost at sea and had documented it in a story, I would want my lost-at-sea-ness to be lost at sea. Or is that just me? Someone call Zay Zee and tell her we’re lost in 2015.

In an era of endless screens—phone screens, computer screens, street screens, TV screens, this screen—patience is no longer a virtue. I don’t have to wait anymore to watch anything that already exists: I type a few keys, fill out a captcha or two, and it’s there for me, served on a screen. This sensation makes seasons, anthologies, and episodes of TV more fleeting. TV shows no longer come on. They’re put on.

When I was a kid, I had two options to watch Dragon Ball: I could either wait for it to play on Toonami, Cartoon Network’s afternoon anime program that we nerds rushed home after school to watch; or go out to Coconuts, the now-defunct music and movies store, and physically buy the season or set of episodes I wanted to watch with the little allowance I had. Following the chronology of episodes was something I had to seek out. Because it didn’t matter if I was caught up with what Goku was doing, or not—unless I had a VHS to pop in, whatever was playing on TV that day was what I was watching. It wasn’t up to me.

And to all the purists out there, I’m talking about the original Dragon Ball; the story of a young boy with a monkey tail named Goku, who would later learn that he A) had superhuman strength; and B) wasn’t human at all. (But that’s revealed in Dragon Ball Z, which the show naturally transitions into). Designed in the beautifully sharp Japanese animation of the late 1980s, Dragon Ball follows the always virtuous Goku as he meets new friends, trains to fight a bunch of bad guys, and continuously tries to locate the seven Dragon Balls, which, if collected, spawn a dragon that grants one wish. (The bad guys, of course, want them, too.) He also has a cloud at his command that he, and anyone else pure of heart, can ride on.

Recently, I faced this sort of stupid, modern quandary: what should I watch?

I’ve never had any interest in rewatching shows of my youth—definitely not streaming CatDog anytime soon—but Dragon Ball, as someone entering their late twenties, stood out to me. It seemed like something fun to do: dive back into an adventure that was very much my own at one point in my life. And now it was widely accessible: all five “sagas,” all 153 20-minute-long episodes, all available to watch at my leisure. It was like having my inner child meet Netflix.

I could return to this universe I once loved, one filled with so many characters, it makes Game of Thrones look like a mini-series, episodes-long fight sequences that somehow feel shorter now, and a steady stream of more content to look forward to in the form of Dragon Ball Z, Dragon Ball GT, the TV movies, and Dragon Ball Super, which is still on. I can watch it the way I always wanted to as a kid, but never could: endlessly and without pause.

And now, onto Cowboy Bebop.

I landed in ’98 – landed in midtown by way of Jersey Transit, and I didn’t like it. It was the gray town I expected, screaming soot into my eyes, bending my neck, leaning me against a payphone as my dad scalped our tickets to Disney on ICE because the buses stopped running before intermission.

Some ten years later, I got into NYU and still couldn’t feel anything for the place. It was never me to be blah about something so big, but I was blah, and when my dad wagged the acceptance letter at me as I was making my bed, I told him to relax.

I watched 27 Dresses and googled through it: “Map of Manhattan” “What is Greenwich village?” “Brooklyn”... Then, in the film’s last scene, the shit sister character reconciles with her ex-fiance and explains that she is broke, making necklaces, and living in Williamsburg. I was FLOORED. What is this bimbo doing in Colonial Williamsburg? What is her business there? She’s become a craftworker? An artisan? They’re not going to explain this? I kept googling.

I laid around the living room when my sister watched Gossip Girl. Hated that. Hated that world of interiors – characters going from dim backseats direct into lobbies with just an establishing shot to give me some air.

I watched Sybil which actually did get me feeling very excited for that Big Apple architecture, baby! A lot of walk-ups in that movie.

Then I watched the movie, a movie meant to be so glamorous, so aspirational and so personal (or so it seemed, for my idea was to study journalism): The Devil Wears Prada.

There’s never been a bigger comedown. It was hopeless. Is there any stirring, any movement in this shiny town that isn’t a dog eating another dog? Is there any story that doesn’t glorify pessimism? Even if the ending seems positive?

I’ve just rewatched it, and my 18-year-old reservations are even more shrill. This Andy Sachs, a fresh Northwestern graduate, has come to New York with a live-in boyfriend, two close friends, and a smile you want to wipe clean off when she says things like, “I need to get to Magnolia Bakery before it closes.”

She’s a girl scout, she’s the high school friend (my high school friend) who visits to complain about allll the walking. She needs teaching, needs to be Pygmalion-ed out of her previous life. It’s satisfying to see Anne Hathaway turn quick, learn some street smarts, lose some weight. But she shows us New York stage-side, waiting by the curtain with a wet wipe. Sure, this is because she has a shitty job, but Andy Sachs would never make the most of this place. She’s certainly not enjoying herself. Nor was she enjoying herself before her reinvention.

So she isn’t willing to sacrifice her morals for the superficial fashion industry, and finally remembers her roots, becoming a reporter for some New York daily. This is the resolution. This girl could not stomach her own success over a vile colleague’s and judged Miranda Priestly’s survivalist maneuvers to remain Editor-in-Chief – a choice to minimally screw over a loyal art director (who still had his job to keep), to provide for her twins as a single mom and to save face.

Rising to the occasion has never looked so much like a fall from grace. Her integrity's been sullied. The audience is meant to be sure of it. There’s no fraction of the multiverse where Andy is still here in the concrete jungle (something I imagine she says to her Boston neighbors, describing her stint in New York), writing and exploring. Why? Because she saw her growth as toxic and practicality as dishonest. She learns to prioritize herself; she finds something to admire in the strong Miranda Priestly, she nearly meets an important editor at the cost of missing her boyfriend’s birthday, but decides, in the end, to protect her innocence. More than innocent, she wants to be consistent.

She can’t stand when friends joke that she’s “drinking the Kool-Aid.” Hey Andy, if you want to drink the Kool-Aid, because you might like the Kool-Aid, and it’s fresher than the water you’ve got, then go on and drink the Kool-Aid! Never mind your college-era friends who reject the Kool-Aid.

Andy sips the Kool-Aid. She returns to the version of herself that her closest friends are most comfy with. She even resumes her college relationship. She reminds me of my first experience of New York City: the 1945 Tom & Jerry cartoon, Mouse in Manhattan. In it, Jerry puts on a boat hat and leaves Tom a note, “This country life is getting me down…”

He takes the train and is instantly astonished at the height of the place. But the lesson is instant, and it’s repeated: don’t you dare enjoy this.

Smiling at the Grand Central ceilings, Jerry gets his ass stuck in gum; riding a breezy bottle cap through street puddles, Jerry is eaten by a sewer; riding the train of lady’s gown, Jerry is dragged through grates. Then, figure skating with an attractive doll, Jerry gets lodged in a champagne bottle which pops him into the New York sky, due east where clotheslines flag over steel trash cans. Jerry parachutes in, using a wilted sock. He lands, he sneezes, he rouses the yellow eyes of the alley – revealing a wiry, vicious cat.

Jerry starts running, he crashes into a jewelry display and is pursued by gunfire, he runs and he runs and he runs all the way back to Tom, rips the note and hangs a sign that says “Home Sweet Home” over his hole.

Nonny de la Peña's Hunger in LA

A new exhibition at the Museum of the Moving Image highlights the ingenuity and optimism of the past ten years of video game design.

If you were to ask me about the history of video games last week, I would have begun with Atari, touched on the delightfully artful CD-ROM works of Theresa Duncan (who I admittedly admired more as a style icon than as a videogame designer), and ended with The Sims 3. I would have assumed having fun was a big part of playing video games. And I would have had no concept of the huge distinction between mainstream games (what you find at GameStop) and the rich, teeming world of independent and experimental games (what you will not find at GameStop). But then I went to the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria and visited the highly enlightening, deeply corrective new exhibit called “A Decade of Game Design.”

The exhibition, which opened on Friday, presents work from eight influential game developers from the past decade, all of whom are working outside the mainstream gaming industry. I was first shocked to see how un-game-like many of the works were. Take, for example, Hunger in LA, developed in 2011 by Nonny de la Peña. The “immersive journalism” piece uses virtual reality to recreate a real-world event that took place at a food bank in Los Angeles, in which one man suffers a seizure and another bolts to the front of the line and steals provisions. In Hunger, you can move around the pandemonium and interact with other people on the scene, all the while hearing audio of the actual event, which was recorded live in August of 2010. The experience is meant to shed light on the hunger and food insecurity many in this country face. I found it moving – especially how it managed to convey people’s sheer desperation.

The other games on view touch on no less weighty themes, including mortality, enlightenment, gender transitioning, masturbation, the history of the gaze, and even the nature of gaming itself. Having fun really isn’t the point – or rather, fun is relative. Because intellectual enrichment can be fun, right? “Unmanned meditates on the banality of contemporary warfare,” reads the riveting description for Paolo Pedercini, Jim Munroe, and Jesse Stile’s 2012 game. In it, the player assumes the role of a soldier controlling an unmanned attack aircraft by day, and by night returns to suburban life. By showing us another type of warfare and its proximity to domestic life, Unmanned cleverly subverts traditional (and popular) military video games. “Are you having fun?” I asked a girl playing it this weekend, who looked to be about 12. “No,” she said, matter-of-factly. But she seemed deeply absorbed.

It was hard, for me, to look back at this decade of impressive work (roughly 2007 – 2017), and not consider the Obama era – a time when so much of American life was taken for granted. As others have argued before me, the relative peace and stability of the Obama years afforded artists the permission to look inward. Though not all the designers in the exhibition are American, most of the games are deeply personal, and interrogate questions of faith, identity, existence, and empathy. Considering the dire political times we’ve found ourselves in stateside – where so many of our basic rights are under siege, so much of our collective energy must be put towards resisting the state, and environmental catastrophe seems all but inevitable – the space to question these things does seem a bit luxurious, though no less pressing.

What will the next ten years of video game design look like, or the next two years and eleven months under an oppressive demagogue? Maybe we will see a return to fantasy and escapism. Maybe games will take a violent or dystopian turn, preparing us for the future to come. Or perhaps virtual worlds altogether richer, more complex, more unexpected, and more limitless will appear, showing us a better way to live in this physical one.

“A Decade of Game Design” is on view at the Museum of the Moving Image through June 17, 2018.

It’s Thursday night and I’m locked out of my apartment. I was heading home to write my Blossom review but instead find myself exiled at the bar. Hello, Lobo!! That’s the name of the bar-restaurant where I end up, my confidence boosted by the two mezcal cocktails I had at my office happy hour.

I explain to the bartender and a waiter idling near my seat that I'm locked out and that I’m writing reviews of Blossom. The bartender does a great Joey Lawrence “whoa.” I’m sitting next to a woman that watched Blossom in her youth. They all seem to know Blossom first hand, even if they haven't thought about the show (or Mayim) in years. None of them are familiar with what Mayim is up to now.

I tell them about Mayim’s content factory and her problematic feminism. The waiter brings up Scott Baio and his recent controversy. All of our cultural memories are so different. I remember Scott from VH1 reality shows. He was always only a dirtbag to me.

I want to dig into something in a later season of Blossom so I download the Hulu app and play “Paris: Part IV” right there. When I finally do get home, I fall asleep watching Parts I, II, and III. The premise of these episodes is that Blossom and her brothers are seeking contact with their mom, who left the family sometime between the Pilot of Blossom and Episode 1. She’s living in Paris, working as a singer in a club.

Honestly WTF. These episodes are so insane. While Blossom discovers her sexuality with a young French man and navigates her complicated relationship with her mother, her two brothers are running around town with the HEAD of a DEAD MAN in a SUITCASE being CHASED by THE MAN IN THE HAT and a mysterious woman.

The brothers are in Bolivia, calling their father from a shady bar, asking to borrow money. To no one’s surprise, the Bolivians present in the episode are depicted unfairly. The real climax comes as the brothers (somehow back in France?) are running to the top of the Eiffel Tower, chased by both the man in the hat and the mysterious woman who both want the suitcase with the head.

The terror of the boys’ experience comes in the form of scenes in the action genre, completely uncharacteristic to Blossom, full of scary foreigners, blow darts and chase scenes. Blossom’s terror comes in the dual forms of the realization that her mother will never live up to her imagined ideal and the death of her sexual naivete. This terror, of course, is never coded as such but is instead dramatized through conversations full of disappointed sighs.

There’s no laugh track in these episodes, so even the jokes that should work fall a little flat. I laugh at Blossom’s jokes alone.

Before she was best known for being THE pop star in a feud with the ACLU, Taylor Swift had a mostly innocent and very popular Instagram persona. She posted photos of her cats Olivia Benson and Meredith Grey, her extravagant Fourth of July parties, and, obvi, her all-star ragtag celeb "Bad Blood" squad. Then in August 2017, she deleted everything she'd ever posted. Swift's Instagram, Twitter, and Tumblr were all wiped clean in a marketing ploy/"Dark Taylor" rebrand just in time for her November 2017 album Reputation. But in establishing her blank slate, she left a gaping hole.

In October 2014, I was not a Taylor fan and then 1989 dropped and I was. It was so fun! Every teen and teen-wannabe I followed on Tumblr was into her, it felt like, and her brand of femininity was one that my predominantly male coworkers glommed onto more so than they did with Kim K Hollywood, a phone game that had been released that summer which I had been hiding in the bathroom to play during work hours. I followed Swift on Instagram, fascinated and then eventually annoyed by her sheer ability to have anyone–even TV stars twice her age–join her sociopathic friend group. Yet, for all the posts I remember enjoying, I don’t remember many specific photos, only a general filter palette and good-girl social vibe. I search on Twitter, type "Taylor Swift 2014" into Google, and, painfully, dive into my own Tumblr archives to find any evidence. She dressed as a Pegacorn for Halloween in 2014, I find, and yeah, I reblogged it, I also find.

It's not about the photo, but the absence of them, the empty listicles comprised of image descriptions that read like alt text for the visually impaired, the Fourth of July party recaps where you can see photos posted by everyone in the squad except Taylor herself and the sterile "This photo or video has been removed from Instagram" placeholder box. Some publications’ placeholders are uglier or sloppier and some don’t have one at all, as if the page doesn't know what to do without a working link. E! Online's embeds are the most interesting to me, as they literally disappear in front of your eyes, transforming from a box into nothing, which is fitting, I suppose. Taylor wanted to be “excluded from the narrative,” didn’t she? She wanted “the old Taylor [to not] come to the phone right now...because she’s dead?”

What now that they disappeared? Is the answer to that really just, “Stop spending time looking at E! Online articles from 2014?” Maybe! Or is it “Look at them more, and get lost in the emptiness lol?” A cursory glance at her underwhelming “Bad Taylor” 2018 IG presence has me learning towards the latter.

TV shows that attempt to portray life in New York City generally take two routes: they’re either about the city or about living here.

Seinfeld falls into the former camp: a show about nothing that could only be set in New York. The fact of George working for a never-seen George Steinbrenner, that episode about the long wait at a Chinese restaurant – these feel like place settings for four nihilists who could only exist here, who are absurd to imagine anywhere else. (This is why, perhaps, the show’s trip to California was only two episodes long.) Girls, on the other hand, is the opposite: it’s a show that tried desperately to pin down who or what a particular generation is, using life in one city as a lense to make sense of Hannah and her friends’ self-aware struggles. (Which is why the trip to Bushwick in Season 1 was less about Bushwick than about the plotlines colliding there.)

Recently, I’ve been watching and loving HBO’s short-lived Bored to Death because it feels like a bit of both: New York City is both its motive and motivation. For context, the show ran for three seasons (2009 to 2011) and starred Jason Schwartzman, Ted Danson, and Zach Galifianakis. (And like Girls, Seinfeld, and most TV shows that exist, the cast is all white and predominantly cis.) It is essentially a stoner crime noir: Schwartzman plays Jonathan Ames, a struggling writer living, drinking and smoking in Brooklyn, who shares a name with the show’s creator and starts doubling as a private investigator on a whim. Ames solves crimes throughout various cityscapes à la Raymond Chandler, but if The Big Sleep met 2009 New York, a city stuck between its pre-financial crisis glitz and its gentrification in the years ahead. Danson (George) is his bachelor magazine editor, while Galifianakis (Ray) is his brooding best friend.

In one episode, Ames cracks a case by drinking a lot of vodka at a Russian restaurant in Brighton Beach. Another episode, guest-starring the great Patton Oswalt and Jim Norton, is titled “The Gowanus Canal has Gonorrhea!” (which it actually did, at the time). Over the course of the first season, George and Ray catch the detective fever too, becoming Ames’ bumbling sidekicks all the while reeling from heartbreak, a high, and a white wine buzz. The show started just before the Brooklyn brand became gag-worthy, so the shots of Grand Army Plaza, the Coney Island boardwalk, and the beautiful brownstone streets don’t feel forced, nor does the multitude of cameos.

In mostly harmless ways, Bored to Death makes fun of the media world, the quickly-gentrifying Brooklyn world, the annoying single white guy world, and other worlds that exist here pushed up against the others, all without taking itself too seriously – much like the city itself, on its best days. There’s an ongoing gag in the show where characters trip over baby strollers entering and leaving any token Park Slope cafe. It’s a stupid, effortless joke. But because it happens often – and really, without explanation – you laugh.